Historical Terms and Why They Matter

Guest blog by No Turning Back advisor Pamela N. Walker

What is in a name? Centuries of Atlantic world history, inherited oppression, and, sometimes, a reclaimed selfhood.

The history of racial terminology in the United States is older than the country itself. Since the early colonial era, terminology for people of African descent, in particular, has evolved, been contested, and remains malleable to this day. Terms such as “Colored,” “Negro,” “Black,” and “African American” have come in and out of usage and acceptance for a number of reasons. To better understand the terms we used in No Turning Back, set in the early 1960s, versus the terms that are acceptable for use today, we must think historically about how and why these terms have changed over time. For the sake of clarity, I will refer to people of African descent across time as Black Americans.

1. “African” and “Colored”

During the early Republic, the earliest mutual aid groups and schools for free and enslaved Blacks adopted the broad term “African” as an identifier. The African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia was founded by Black freedman Richard Allen while the African Free School in New York was organized by founding fathers Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. In the Emancipation Era – the post-Civil War period of new-found freedom and autonomy for the formerly enslaved – Black Americans shifted from inherited terms of racial categorization to naming themselves. “Colored” was the dominant term through the mid to late 19th century, but freedmen adopted the term for themselves as a marker of race pride. Historians trace this seemingly preferred designation through Black-led organizations such as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (1896) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) that sprang up around the turn of the century.

2. “Negro”

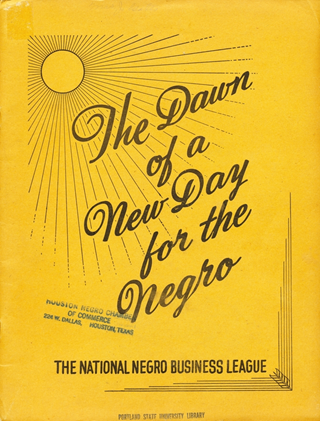

The word “Negro” was born from romance languages (French, Spanish, Latin, and Portuguese) and literally means “black” or “dark,” but its usage as a description of people dates back to Spanish colonization. Spanish colonial “casta” or caste systems hierarchically categorized European, Native, African, and mixed-race populations in North and South America. The term “Negro” gained acceptance in the late 19th century with the promotion of Black activists like W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes’s affirmation of the term (and celebration of the race) is evident in this piercing line from a 1926 essay: “Why should I want to be white, I am a negro – and beautiful.” “Colored” and “Negro” were used somewhat interchangeably by Black Americans, but by the 1940s, there were no new organizations that included the term “Colored” in their title, indicating another shift. Instead organizations such as the National Council of Negro Women (1935) and Negro Youth Congress (1937) became commonplace. Black activists preferred “Negro” over “colored,” as the latter lacked specificity given the growing racial diversity of the country. “Negro” also encompassed those with African ancestry and was preferred over “mulatto,” another inherited word of Spanish origin that was considered offensive by the 20th century.

By 1950, while “Negro” was the dominant term by which Black Americans dignifiably identified themselves, it was not without tension. In addition to its origins within the Spanish colonial caste system, the word has an even more complicated history because the derivative racial epithet came into fashion during the 1800s and for many, remains extremely offensive today.

3. “Black” and “African American”

By the start of the modern civil rights movement, Black Americans were considering new ways of thinking about their communities. “Black” had been used as a negative foil to “white” [people], and thus the opposite of all that is “good” and “pure,” and for that reason has been considered offensive. However, in the 1960s, a movement led by young people sought to pridefully reclaim the term: Black Power, Black is Beautiful. While Negro was an inherited term associated with slavery, Black was a chosen identity rooted in self-determination and embraced natural hair as beautiful. For Black Americans who experienced “white supremacy” through lynching, pogroms, and all types of violence, “Black” as the antonym of “white” was indeed a good thing. The use of Black by young people, student movements, and organizations like the Black Panthers added to the intergenerational conflict already emerging within the civil rights movement around strategy and the pace of change. But by the late 1960s and 1970s the identifier was common, appearing in Black studies programs, Black cultural centers, and Black associations across the country, and remains acceptable today.

Around the late 1980s, the term “African American,” which originally appeared in public as far back as 1835, returned to the American lexicon to center cultural integrity and heritage. Despite its popularity among educators, writers, and political leaders, this term can be tricky because many Blacks in the United States, whose ethnic, cultural, and national background allows for greater specificity, do not identify as African American (e.g., Jamaican American, Nigerian American, Ghanaian American).

4. No Turning Back and Today

The designers of No Turning Back made a choice not to use terms that would be out of place and even offensive to the people depicted in the game. Many Black people in the early 1960s were still proud of, and fighting for, the use of “Negro” and its capitalization, which signified dignity and respect. While the terms “colored” and “Negro” were once acceptable terms when referring to people of African descent, today these terms are often considered offensive and are unacceptable. Instead, you should use the terms African American or Black, as in a Black person (or a Black woman, a Black man, a Black student, etc.), even when discussing this history.

To learn more, check out these resources:

- “The Journey From ‘Colored’ To ‘Minorities’ To ‘People Of Color,’” by Kee Malesky, NPR Code Switch, March 30, 2014

- Stamped from the Beginning and Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, by Ibram X. Kendi. A kids’ version of this book is available for younger readers, as well as an educator’s guide.

- Making Black America Through the Grapevine, a four-hour documentary series from PBS

- No Turning Back Educator Guide

Pamela N. Walker is an Assistant Professor of History at Texas A&M-San Antonio. Walker received her PhD in African American and Women’s history from Rutgers University. She is currently revising her manuscript ‘Signed, Sealed, Delivered: How Black and White Women used the Box Project and the Postal System to Fight Hunger and Feed the Mississippi Freedom Movement,’ which examines motherhood, race, activism, benevolence and political consciousness in 1960s-era women’s social movement networks. Walker has contributed articles all three volumes of the award-winning Scarlet and Black Project at Rutgers University. Her work has been supported by the Mellon Foundation, the American Philosophical Society, the PEO Sisterhood and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Walker served as a lead advisor on Mission US: No Turning Back.