Marching Home: Honoring Family Stories and Civil Rights in the Mississippi Delta

Guest blog by No Turning Back advisor Pamela N. Walker

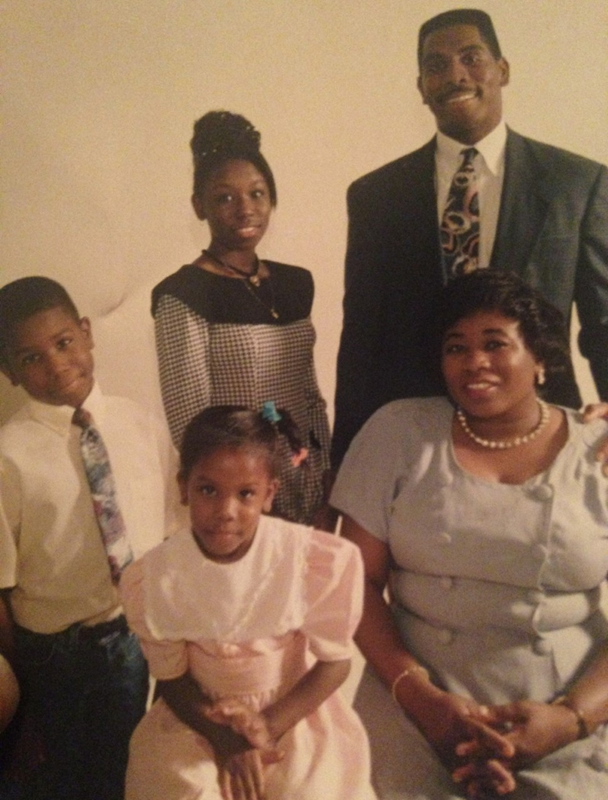

I know Mississippi, the Delta specifically, very well. Every Easter, every Thanksgiving, every Christmas, and long weekends and holidays in between during my childhood were spent driving up Highway 61 or down Interstate 55 to both of my grandmothers’ homes in Sunflower County. On the way there, I would sit in the back middle seat (youngest child problems!) and learn my family’s story. The stories of my parents, who were neighbors and eventual high school sweethearts, were most often laden with sibling mischief and revelry of their large families in small homes. Daddy spent his days with a squad of brothers shooting hoops in the sweltering heat, while Mom made paper dolls and eventually learned to sew in a household mostly full of girls. The stories were mostly playful: basketball games won (some lost), sneaking baby turtles in a pocket on the way to third grade, searching for hidden quarters in a cotton field, proudly wearing a homesewn dress to prom. Other times the stories revealed hard truths of being Black children in the South: attending segregated schools, chopping cotton every summer with a league of siblings to help ends meet, losing an 8th grade classmate – Homer Tiny – who was killed for purportedly trespassing on the property of a powerful white man.

This was my understanding of Black life in the 1960s and 1970s. The knowledge of any “movement” and activism in the Mississippi Delta came later. In grade school, of course, most teachers bypassed local history, in favor of the broad national narrative of the movement. I learned of a civil rights movement through figures like Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and others who are now etched in mainstream iconography. But the story of the civil rights movements and the daily lives of Black Americans is much more. It is much closer to home for so many of us. It would be years before I learned the history of sharecropper-turned-organizer Fannie Lou Hamer, who lived just two towns over from where my parents were raised, joined with student activists to register voters, and built a cooperative farm for poor Mississippians. Outside of school, I’d have to do my own digging to learn of Medgar Evers, the NAACP state field secretary who investigated the murder of Emmett Till and discrimination at food distribution centers. I would not meet Sam Block until I became a historian myself, deep in the archives, researching SNCC activism and antipoverty efforts in Greenwood, Mississippi. These folks, from my home state, represent the movement too. They fit within the local and the national story.

No Turning Back centers the local as a part of the national narrative of the civil rights movement. Local stories like the ones from the game allow us to understand the experiences of those who lived through them. No Turning Back allows us to view Mississippi and the Movement through Verna’s eyes. While Verna is a historical composite character, the encounters she has are based on real people, adolescents who were around during the era who joined the movement and ordinary children like my parents who navigated the Delta during a tense time. The activists Verna meets – Medgar Evers, Sam Block, and others – are real. Their actions and lives can be investigated further in biographies, books about the movement, and in archives.

The local and the national narratives as well as the ordinary and extraordinary are often separate. No Turning Back holds the local and national, the ordinary and extraordinary together, allowing us to consider networks of communication and learning and transformation. No Turning Back will likely allow some students to make connections between the broader movement and their personal family histories that perhaps have gone untold.

Check out these resources to learn more:

- SNCC Digital Gateway: “The Story of SNCC”

- Mississippi History Now: “When Youth Protest: The Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, 1955-1970″ by Dernoral Davis

- Educational Materials from the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

- PBS American Experience: Freedom Summer Documentary

- Hill, Karlos K, and David Dodson. 2021. The Murder of Emmett Till. Graphic History Series. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Moye, J. Todd. 2004. Let the People Decide : Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. Heinonline Civil Rights and Social Justice. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Payne, Charles M. 2007. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom : The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- No Turning Back Educator Guide

Pamela N. Walker is an Assistant Professor of History at Texas A&M-San Antonio. Walker received her PhD in African American and Women’s history from Rutgers University. She is currently revising her manuscript ‘Signed, Sealed, Delivered: How Black and White Women used the Box Project and the Postal System to Fight Hunger and Feed the Mississippi Freedom Movement,’ which examines motherhood, race, activism, benevolence and political consciousness in 1960s-era women’s social movement networks. Walker has contributed articles all three volumes of the award-winning Scarlet and Black Project at Rutgers University. Her work has been supported by the Mellon Foundation, the American Philosophical Society, the PEO Sisterhood and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Walker served as a lead advisor on Mission US: No Turning Back.